Stirling and the East India Company: Part 2 Nabobs and Civil Servants.

So you will remember that Part 1 explored the initial invasion and context of the tremendous wealth carved from India. This second part examines some of the individuals who came back with that money but also the next wave of traders and settlers who formed the Indian Civil Service.

Lets again start with Sir Walter Scott who was aware of both the wealth and dangers of India, he talked of his ‘young griffins’ who would go to India for opportunity and success but was wary they would come back as nabobs. He also didn’t really want his own children going there, as there was really no need, he could use his own influence to advance his children’s career. This is the crucial point…as he noted ‘we poor gentry must send our younger sons’, you only went if there was no other option.

A number of young men whom Scott took under his wing, including his son-in-law died in India. Perhaps the most astonishing of these people of these people was John Leydon, perhaps the quintessential lad o’ pairts.

Leydon was the son of shepherd who studied divinity, but grew bored of it and then started collecting border poetry and songs for Walter Scott. He then studied medicine and went to India. He was first appointed as naturalist to survey Tipu’s former kingdom of Mysore. He then developed a taste for languages and began translating Persian, Arabic and Hindustani. After this he was appointed a Judge! Now I suppose there are two ways to look at Leydon, he was certainly incredible but was he really that good to be able to straddle four different professions (law, medicine, cleric and philologist) or perhaps was he simply the best of a limited bunch? Regardless he died at 36 on a trip to Java after entering a library that had not been properly aired…..!

Many however, were successful and the money flowed back to Scotland. In 1806 The Edinburgh Review remarked on the return of investment in India ‘in the fruit of a Nabob, who fixes it in a palace which he builds in the neighbourhood of his native city, on his return from Asia.’

In Stirling’s case we have at least two such palaces.

The first and most impressive of these was Airthrey which was acquired by Captain Robert Haldane who is often said to have been the first Scot to become an East India Company Captain. He was described as "an arrogant, ambitious, purse-proud man" who bought the estate in 1759 with the intention of creating a modern fashionable residence. His nephew another Robert Haldane inherited the estate and commissioned Robert Adam to build a house and estate. Famously he tried to skimp on the fees and Adam left the project. He also built a hermitage on the estate and advertised for a hermit. There are two versions of the story…the first is that no one applied and the second is that the hermit was fired after going drinking in Bridge of Allan! The estate was sold to another nabob Sir Robert Abercromby who had fought in America and India and had been The Governor of Bombay. Eventually of course the estate would become Stirling University.

The second estate lies to the east of Stirling in what is now called Plean Country Park, currently owned and managed by Stirling Council. This estate was also initially owned by the Haldanes who then sold it in 1799 to Francis Simpson another East India Captain. He built the house in 1819. Unfortunately over time the money ran out and the building became dilapidated.

Now not all of the Nabobs became fabulously rich, some were more modest and so only smaller amounts of money came back to Stirling. Locally Touch House, Auchenbowe House and Airth Castle were owned and improved by people who made money in India. Sometime it was even more modest….this is the Jaffray memorial which was paid for by William Jafffray of Bengal to his father and brother. William Jaffray’s fate is not recorded.

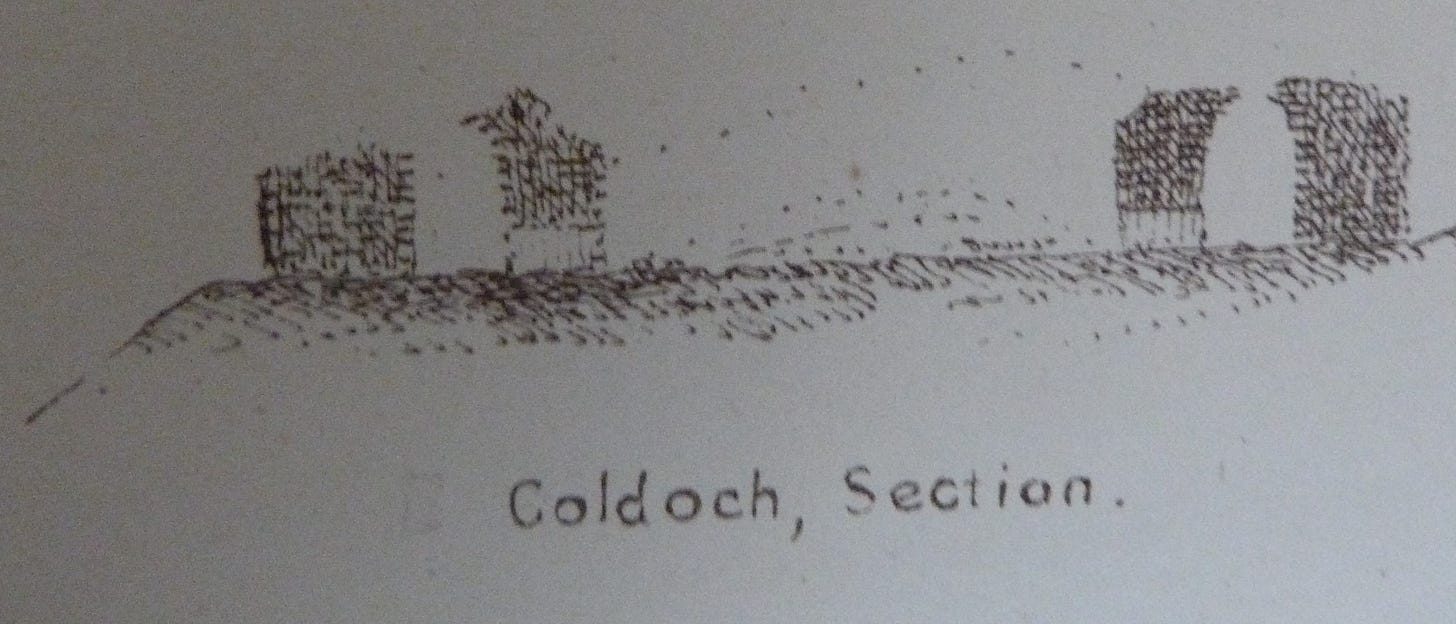

Now of course not all merchants lived to send money back to Scotland, some died out there and there family inherited that wealth. This happened with Christian MacLagan, who used the wealth derived from her brothers’ businesses to free herself from contemporary shackles, she studied archaeology, she paid for a church and her own house where she carved the fireplaces. The money allowed her far more freedom than she ever could’ve had on her own. For me her crucial role is as one the world’s first modern archaeologists, she is probably the first to dig in a manner we would recognise today and was the first to consider brochs houses. Indeed she persuaded the inventor of chloroform Sir James Young Simpson to dig the broch at Coldoch…though he left her out of the report.

MacLagan’s record of Coldoch, perhaps the world’s first archaeological section.

Given the size of India there were by necessity a vast array of professionals and the various memorials of the Top of The Town Cemetery in Stirling list Scottish officers of the Indian army and navy, as well as ship captains, surveyors, missionaries, surgeons and judges. A vast interconnected network. Of course we only see the people who came back to Stirling (or who left grieving relatives) many stayed in India while others migrated southwards to England. As one reads accounts of these people and their lives its odd to note that their identity morphed and the became part of England, Scotland like India was now part of a successful world spanning Empire. A rejection of this, or at least a need to strengthen Scottish identity lay behind the National Wallace Monument…the largest ever monument built to Scottish Nationalism and the biggest monument to a single person in Britain.

However, before exploring these networks you had to get to India and this, as we heard in Part 1 was very hazardous. The Valley Cemetery contains the graves of two people who died on shipwrecks to India. Thomas Somers died off the coast of Ireland on the way to Bombay on the steamship Clan McDuff in 1881 after the ship sprang a leak. The ship had 19 passengers and 46 crew of which 32 including Thomas drowned. Another ship the Ariadne made it to India only to sink in the River Hoogley, which flows into the Bay of Bengal in 1850 and its Captain Thomas Goodsir

So I promised you details of how just interconnected all of these families were and there is no better example than Abercromby Dick. He was a judge in India at the Sudder Dewany and ended up retiring in Bridge of Allan and his house stands to this day. This court used British judges to interpret Indian law and a list of Dick’s judgments and accounts of his cases can be found here.

Dick’s father was born in Logierait Pert in 1757 and married his wife Charlotte MacLaren in Calcutta. He was a Surgeon for the East India Company and worked for Sir Robert Abercromby, who we heard of in Part 1 and was one of the owners of the Airthrey Estate. The pair had seven children, all born in India and four of whom died there. The eldest was the celebrated General Sir Robert Henry Dick and the youngest was Abercromby, who was probably named for Sir Ralph. Robert met Napoleon and fought in India and Waterloo and had a distinguished war record and died in the Sikh War, mopping up yet more ‘obstacles’ to British rule.

Abercromby was as we’ve heard a judge who helped defend one of Tipu Sultan’s children: Prince Ghulam Mohammed (and we will hear more of him in Part 3). The family was well integrated into the upper echelons of British Society: his sister Eliza Dick was a minor poet and friend of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Abercromby had met Thomas Carlyle. As an aside all of Carlyle and his wife Janes Welsh Carlyle’s letters are published online and represent an incredible insight into Victorian Britain.

In summary, its clear that for Scots and Scotland, India provided not just wealth, but opportunities to climb social ladders, to break social conventions, to become well known military heroes, to meet poets and philosophers and in some cases to become English. It allowed Victorian society to fool itself that Britain was a just land where those with talent could advance and break through social barriers but of course it all came a terrible price for the Indians and one that they were not always willing to pay.

Part 3 will examine resistance and rebellion (?) to British rule.